Mental health treatment is rarely a straightforward process. Shifting priorities, life events, and new issues turn therapy in different directions all the time. When that happens, a good treatment plan can be a road map that helps you and your client navigate these changes.

Most therapists use treatment plans when billing to insurance companies, because they give a concrete justification for each session. But treatment plans don’t just have to be about paperwork; when they’re done well, they can be an integral part of what makes your process successful. Below are some general tips for creating a solid treatment plan, plus some ways to tailor them to fit your client’s needs.

Steps to developing the right treatment plan

Ideally, every client should have a personalized treatment plan. While you might decide to start with a template, you should go on to carefully craft each plan based on the screening and assessment process for each client. Here are those steps in more detail:

1. Screening

Screening happens when new clients contact you, and give you a brief overview of the issues bringing them to therapy—via a form on your website, a phone call, or a free consultation. While it might be tempting to take on every client that wants to see you (especially when your practice is new), your treatment plan will only be as good as your skill set. Screening out clients you’re not comfortable treating will leave more room for clients you feel confident you can help.

In addition to determining whether or not you’re comfortable treating them, the screening process will also determine what conditions you assess them for. Getting the whole picture right off the bat can avoid initiating the wrong assessment and treatment, and going down a rabbit hole of ineffective therapy.

2. Assessment

Once it’s clear what general issues your client may have, it’s time to assess them. Assessments are all about getting a more detailed picture of the severity and nature of their problem. For example, once you’ve determined a client has anxiety issues, an assessment can determine whether or not they have specific phobias, panic disorder, or co-occurring issues like substance use disorders. Suicide risk assessments should be a part of the process as well.

Your assessment will help inform your treatment plan, since it will help you pinpoint the exact interventions your client may need. Whether your assessment is a questionnaire or a more general conversation, it should result in a clearer understanding of what specific issues your client needs help with.

3. Treatment plan

Once you have a detailed assessment, you can begin drafting your treatment plan—collaboratively with your client where possible. When treatment is based on the client’s goals, they’ll be much more motivated to follow through with the assigned tasks between sessions.

It’s also important to remember that your client’s treatment plan shouldn’t be set in stone. As your client progresses through therapy, return to your treatment plan to record their progress periodically. That way, you’ll have a clear record of what you tried, what worked, and what didn’t. The specific elements you should include in a treatment plan will vary, but below are some of the broad strokes of any good treatment plan.

Current information

A treatment should include a summary of all of the current information you have on your client, including contact information, emergency contacts, and community care providers. You should also include the results of your assessment, and any past diagnoses and treatment.

As your client progresses though therapy, they may open up about past traumas or other events significant to your work together. Keeping a running overview of this at the top of your treatment plan can help you maintain a trauma-informed practice, and avoid interventions that will retraumatize these clients.

Goals and Objectives

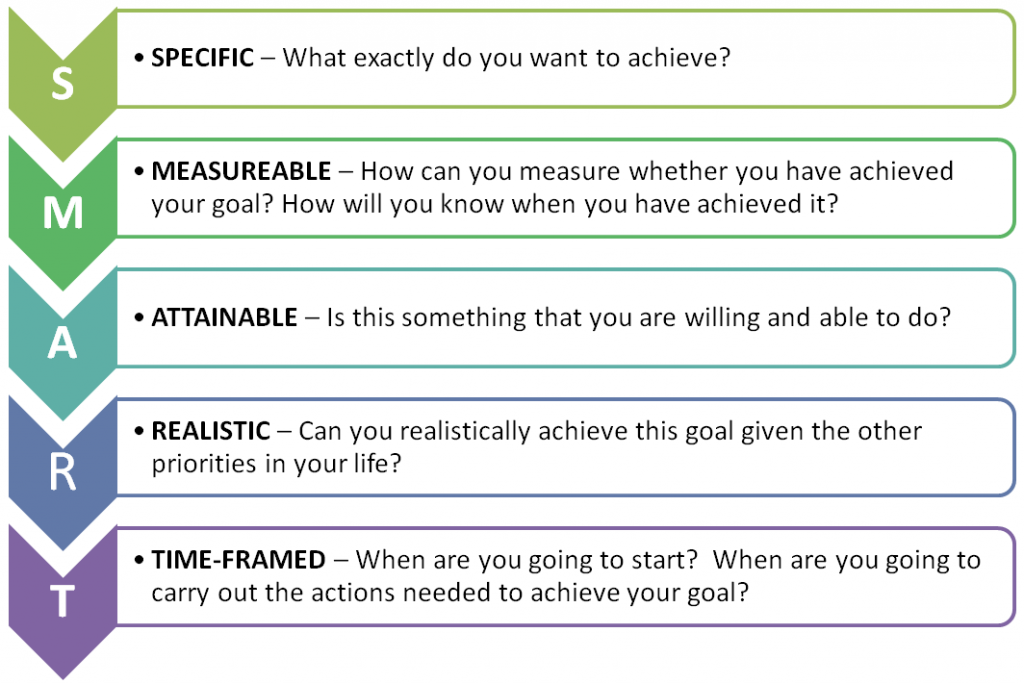

The bulk of your treatment plan should be the goals of your work together, broken down into more specific, actionable objectives. For example, if you’re doing exposure therapy with an agoraphobic client, their first goal might be to just go near the environment they usually avoid, while the second goal might be to walk through the door. Aim to use SMART goals that are Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, and Time-Bound:

Specific – Goals should identify specific behaviours or situations they’d like to change. For example, if your client comes to therapy to improve their relationship with their spouse, ask them to imagine exactly how they’d like the relationship to be different at the end of treatment.

Measurable – Try to come up with a way of measuring how you’ll both know when your client has achieved the goal or completed the objective. This could be a measurement of a specific behaviour (reducing the number of drinks per day, for example), or a rating on an assessment.

Attainable – Sometimes it’s not realistic to anticipate that someone will recover completely; an attainable goal might be managing ongoing symptoms rather than completely eradicating them. You may find you need to adjust goals and expectations to make them more attainable for a client who can’t complete the objectives you started with.

Relevant – The goals in your treatment plan should be relevant both to the therapeutic process and to the client themselves. This is particularly true for therapists using a person-centred approach. If you create goals that aren’t important to your client, you’ll have a much harder time getting them to achieve them.

Time-Bound – Goals and objectives should be on a set timeline; periodic reviews and adjustments can be made along the way. Make a section for the anticipated completion of each objective and the actual completion date, so you know how accurate your initial projection was.

These goals and objectives should be mapped out according to two variables: what the client will do, and what interventions the you will contribute. That way, you’ll be able to prepare for each session by refreshing your knowledge on the specific interventions you plan along the way. Your client will prepare by practicing the skills you assign them. This is sometimes conceived of as a contract between you and your client, that you both sign.

Progress and Outcomes

Tracking treatment progress and outcomes in your treatment plan will help you know when therapy is working and when it isn’t. Sometimes you need to change tactics, alter goals, or even refer your client to someone else. Tracking progress also lets you update the remaining treatment timeline, which can be particularly important if your client’s insurance is only paying for a limited number of sessions.

As a part of monitoring your client’s progress, consider collecting feedback from them at the end of each session. Although some therapists can be resistant to collecting feedback from clients, new research suggests that it can help avoid negative therapeutic outcomes. Feedback you collect from clients should ideally include routine outcome monitoring throughout treatment. Clients can often be shy about giving truthful feedback face-to-face, so using remote surveys can give therapists a more accurate picture of how effective treatment is over time.

Treatment plans for specific disorders

The length and goals of any treatment plan will vary a lot depending on the client and the issues they bring to the table. For example, schizoaffective clients may need long term, integrated treatment planning to streamline multiple care approaches, while a client with a minor behavioural issue might need a short, solution focused approach.

A generic treatment plan can be a good starting place, particularly if you’re treating multiple types of mental illness. You can tailor an unspecified treatment plan to fit the specific needs of each client—below are some examples of different treatment approaches and associated goals for treatment planning.

Substance abuse: this often requires treatment planning for both substance abuse issues and mental health issues. For people on the milder end of the substance abuse spectrum, goals could include 12-step programs or other community services. For more severe cases, treatment plans would ideally integrate with detox and rehabilitation centers.

Some examples of substance abuse goals might be:

- Find alternative ways of coping with stress or substance use triggers

- Identify and treat co-occurring mental health issues alongside the addiction

- Explore ways to change current lifestyle to establish and maintain sobriety

Self esteem: since low self-esteem is often a symptom of a larger disorder, treatment planning could focus either on the underlying disorder, or on cognitive and behavioural approaches to create outcomes that improve self esteem.

Some examples of goals to increase self esteem might look like:

- Identify personal strengths and find ways to use them more often

- Challenge negative interpretations of self with positive self talk

- Cultivate more positive relationships that contribute to growth of self esteem

Anxiety: clients with anxiety may be facing generalized anxiety, social anxiety, phobias, or a panic disorder. Treatment plans could range from short-term exposure therapy for specific phobias to longer term work that addresses negative thought patterns that might contribute to anxiety.

Some anxiety-related treatment goals might be:

- Gradually increase tolerance of a specific task or situation (flying, public speaking, etc)

- Make lifestyle changes that contribute to lowering anxiety

- Work together with client to increase ability to cope with anxiety in the moment

Depression: approaches to treating depression might use Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), Behavioural Activation, or a combination of approaches. Treatment will depend on the severity of depression established in the assessment and whether or not there are other co-occurring disorders.

Some examples of goals for clients with depression might be:

- Increase actions that lead to positive reinforcement of healthy patterns of behaviour

- Reduce or eliminate suicidal thoughts or self-harm incidents

- Engage family members in a system of collaborative care

Employment: Individual Placement and Support therapy can help those with serious mental illnesses find stable part-time or full-time employment with the help of community services. Therapists offering career counselling to clients with less severe issues may decide to opt for a solution-focused approach to address issues like career indecision.

Some goals for employment-related therapy might include:

- Determine the best community employment resources the client can access

- Decide on short term, intermediate and long term employment goals

- Explore income assistance or disability income options where necessary

Anger Management: treatment often involves helping clients to identify anger triggers, then to explore ways to stop and channel their anger into more productive actions. Clients in anger management therapy can range from violent offenders to people with a traumatic brain injury, to children with bullying problems.

Some goals for anger management therapy might be:

- Reduce the frequency and severity of angry outbursts

- Uncover emotions hidden beneath the surface of anger if applicable

- Develop healthy coping strategies that offer alternative ways to direct anger

Schizophrenia: since clients with schizophrenia need medication to manage their symptoms, treatment will ideally be collaborative with other health care providers in the community. This may take the form of assertive community treatment (ACT) or another intensive treatment model. Treatment is usually long-term management, with a high risk of disengagement which can result in devastating outcomes.

Schizophrenia treatment plan goals might include:

- Stabilize hallucinations and delusions with antipsychotic medication

- Establish a collaborative care team in the community to work with the client

- Develop coping skills to increase adaptive functioning and reduce residual symptoms

Borderline Personality Disorder: clients with Borderline Personality Disorder also have complex treatment needs; the most common treatment for BPD is Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT), which combines individual counselling with in-the-moment phone sessions and group skills training. This disorder creates multifaceted issues requiring long-term treatment and more frequent sessions.

Treatment goals for Borderline Personality disorder might include:

- Increase ability to regulate emotions

- Improve interpersonal relationships and/or employment stability

- Reduce compulsive behaviours such as binge eating, compulsive spending, etc.

Bipolar Disorder: oftenrequires mood stabilizing medication in conjunction with helping clients learn how to manage their symptoms, identify manic and depressive episodes, and continue to stay on their medication. Treatment will vary depending on whether the patient has Bipolar 1 (characterized by mania) or Bipolar 2 (characterized by hypomania).

Some goals for Bipolar Disorder could be:

- Promote psychological stability with regular habits using IPSRT interventions

- Identify early signs of manic or depressive relapses to prevent them

- Find mood stabilizing medication that works for the client

Behavioural Health: behavioural health treatments address addictive, compulsive, or other unwanted behaviours such as gambling addiction, internet addiction, or behavioural problems in children and youth. Behavioural health treatment plans tend to focus on concrete, behaviour-based goals.

Some goals to treat Behavioural health problems could include:

- Help client to avoid unwanted behaviours through aversion therapy

- Find positive alternatives to negative behaviours (for example, replacing alcohol with soda)

- Increase feelings of empowerment/control over behaviour with CBT

Agoraphobia: agoraphobia falls under the general umbrella of anxiety disorders, and typically occurs with panic disorders. Treatment usually involves CBT or trauma-based work to examine thoughts and behaviours related to avoidance, and exposure therapy to help clients become habituated to the environments they avoid.

Some goals to treat Agoraphobia might be:

- Reduce panic symptoms with medication

- Gradual exposure to the feared environment until it becomes tolerable

- Teach client coping strategies to manage anxiety and panic symptoms

Schizoaffective Disorder: treatment for schizoaffective disorder is complex, managing both the hallucinations or delusions and mood issues. Often, people with schizoaffective disorder are at risk for co-occurring substance disorders, and will need community treatments to help them manage their illness. Treatment is often a combination of both mood disorder and schizophrenia treatments.

Goals for treating schizoaffective disorder might include:

- Work with the community to secure stable housing, employment, or benefits

- Find medication to help manage symptoms of the disorder

- Skills training to help manage symptoms of the disorder and day to day tasks

Narcissistic Personality Disorder: as with most personality disorders, NPD can take a long time to treat. NPD treatments may include transference-focused therapy or a combination of approaches, helping the client create a more integrated sense of self.

Goals for narcissistic personality disorder might include:

- Improve interpersonal relationships

- Generate a more realistic perception of self

- Treat co-morbid issues such as depression or anxiety

Treatment plans are the road map—but it’s up to you and your client to drive

Ultimately, it’s important to remember that treatment plans are just one facet of good therapy. They can’t replace the rapport, compassion, and solid boundaries that a good practitioner maintains every day. But done right, they can be a valuable way to help keep your practice professional, compassionate, and safe. And most importantly, they map out your client’s path to recovery.